Faced with a cost-of-living crisis, rising delinquency, failing public services, and riots in the suburbs, the French government has finally sprung into action – it’s banning smoking outdoors. Not entirely, of course, just in places where children might be. The new rules, coming into force in July, prohibit lighting up in any space “frequented by children,” which is as vague and self-important as it sounds. We’re told this includes parks, beaches, bus stops and sidewalks near schools. Where else? No one knows. What is clear is that the state is now more concerned with puffing parents, than with knife crime or collapsing hospitals.

The announcement came courtesy of the minister for labor, health, solidarity and families, Catherine Vautrin, who described it, without irony, as a “new dynamic” in France’s anti-smoking campaign. It’s hard to imagine a better illustration of political displacement. Unable to fix anything that actually matters, the French state contents itself with issuing €135 fines ($150) to middle-aged women having a Marlboro Light on a bench.

This isn’t really about second-hand smoke. It’s about control, dressed up as compassion

The rationale is, of course, health. But the real objective seems to be moral purification. France is trying to smoke-shame us into righteousness. It’s no longer enough to discourage smoking, smokers must be pushed out of sight. What was once a vice is now treated like public indecency. This isn’t really about second-hand smoke. It’s about control, dressed up as compassion.

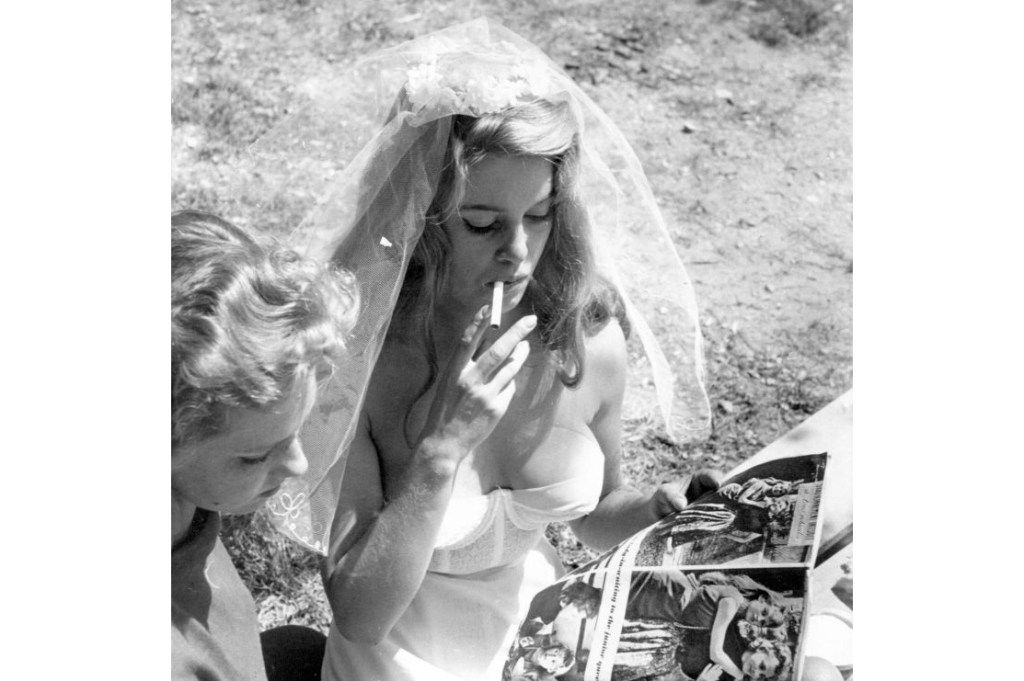

The country once romanticized the cigarette as a symbol of insouciance and rebellion. France smoked with style. Remember Jean Gabin and Brigitte Bardot, smoldering through scenes, cigarette in hand. In the early 2000s, cigarette haze in restaurants, and even cinemas, was as much a part of Paris as zinc countertops and surly waiters.

Now, though, the mood’s changed. Anti-smoking campaigns have been joined by aggressive taxation, with packs now averaging €12.70 ($14.50). That’s over twice the price of 15 years ago. And yet, despite the crackdown, France still insists on a cultural exception. Smoking may be banned at the beach, but on a café terrace, it will remain not just tolerated but ritualized. A Gauloise with your morning espresso will still, somehow, be part of the national DNA.

Maybe the government realized it couldn’t quite get away with banning smoking on terraces. You won’t be able to smoke on a beach, but slide into a wicker chair with a noisette, right up against other patrons (children included), and suddenly your cigarette is safe again. The state may rule the streets, but the terrace belongs to the people. Ironically, café terraces are the only place where second-hand smoke bothers me. Perhaps it’s the wind always blowing in the wrong direction.

This selective puritanism is uniquely French. It’s moral in tone and arbitrary in application. Britain, by contrast, treads a less dogmatic path. Smokers pay dearly for the privilege – on average £16.50, or $22, a pack. But smoking in outdoor spaces remains largely unregulated. Beer gardens and pub patios are still safe havens for smokers, and while some schools ban smoking nearby, there’s no nationwide dictate against smoking away in parks or on beaches.

How France will enforce these new rules remains murky. Will gendarmes patrol parks, fining rogue pensioners with Lucky Strikes? Will lifeguards turn snitches over a stray Camel? France’s 2008 indoor ban saw uneven compliance at first. I recall getting into plenty of arguments at the time with smokers blatantly ignoring the new rules. This outdoor gamble feels even shakier.

What began as health policy now feels like a moral crusade, or perhaps even social engineering. You’re not just lighting a cigarette, you’re committing a civic transgression. While this ban is dressed up as protecting children, its true target is the adult who still thinks they should be allowed to behave like one. Can’t adults decide for themselves if their beachside cigarette might bother anyone nearby?

France’s technocrats, like their counterparts in Brussels and Westminster, have discovered that once you frame something as “for the children,” it’s nearly impossible to oppose. Resist it and you’re selfish. Question it and you’re dangerous. It’s about the symbolism. The adult must be reformed, the pleasure neutralized.

This is what Macron’s government does best: a crackdown for the cameras, a reform for the press release. The real vice isn’t tobacco, its liberty taken too far. And perhaps that, more than cigarettes, is what the state wants to extinguish.

So when in France, light up – if you must – but do it sitting down, espresso in hand, in one of the few places left where the government hasn’t yet confiscated adulthood. For now.